Protectorate „Böhmen and Mähren“, Terezin, Dachau – Feierabend’s family

Memories of Vladimir Feierabend

The protectorate Böhmen and Mähren was a grim time for our family. Uncle Lada became a member of the Czechoslovakian government as a minister of agriculture. Also, he had joined the underground against Nazism, a movement called “Political Headquarters”. At the beginning of the year 1940 he was warned by Prime Minister Gen. Elias that his involvement in this movement was revealed and his life was in danger. With the help of Czech and Slovak patriots he managed to escape under dramatic circumstances which he described in detail in his memoirs. He travelled eastwards through the Balkan, then to France and eventually he arrived in England where he became a member of the Czech government in exile. This had consequences for our part of the family. The Gestapo looked for uncle Lade at our flat and we did not know whether the situation would turn against us.

At the time I was 16 years old and I attended the gymnasium at Kremencova Street. I started playing basketball for UNCAS, was a member of the Scout movement and of the YMCA. That year I did not go camping with them because there was always the worry what could happen at our home. Later my father was arrested by the Gestapo in connection with my uncle’s escape, because they suspected that he assisted him. He was jailed in Prague Pankrac and was then sent to Munich to the Stadelheim jail. It was not an easy time for our mother, me and my brother. As a result of all the stress, my school grades deteriorated, but at least I kept playing basketball with great success. We got lots of support from our extended family and we were very grateful for it.

Our father was released from jail on 6 March. He was so thin that he could easily wear my brother Karel’s clothes. Unfortunately, our joy did not last long. Nazi terror increased with the arrival of Heidrich, a new leader, who introduced martial law and condemned many people to death. Heidrich’s assassination in May of 1942 led to bloody revenge. People started to really worry about their lives. We managed to celebrate my father’s 50th birthday at home.

In 1942 the school year was extended by two weeks to make up for longer winter break caused by coal shortage. As a result, we did not finish school year until 15 July. I just finished septima (7th grade) and my brother Karel finished the second year of his post graduation course in civil engineering at the technical college. All Czech universities were shut down after 17 February 1939, the date of the student uprising. At school I was trying my best to achieve better results, but the German language in particular I found quite uninteresting. I really had to catch up at the end of the school year.

It was 1 July, a beautiful summer day, when I was finishing my studying for the day so I could go play basketball in Sokol hall at Mala Strana . Only five of us promised to attend the training. After lunch, mother went to Spalena Street to visit her mother, father was at his office. At about three o’clock somebody rang the bell. I went to open the door. It was our grandfather, who lived downstairs and there were two men from the Gestapo with him. He told me that he was being taken for interrogation, asked me to tell my parents but not to worry. As I mentioned before, all Gestapo activities greatly increased after Heidrich’s assassination. I was worried that the interrogation was somehow connected with Uncle Lada’s work in London as parachutists were sent from England. Grandpa was driven away, and I carried on with studying, ironically, Hitler’s biography. I was not worried that they would do something to grandpa, since he was 81 years old.

About an hour later the bell rang again. I went to open the door and again there were 2 men from the Gestapo. They asked me to go with them, so I took my personal necessities and followed them. I started to worry. I wrote a note for my mother that I was at the Gestapo at Bredov Street, room no 142. On the way there we stopped at Spejchar where Aunt Hana and her family were living. After a while, the Gestapo man came back because Aunt Hana was not at home. Then we drove to Petrske square to the technical school, where my brother Karel had his afternoon lessons. They were obviously well informed. When they brought Karel to the car, he looked at me questioningly. We were all silent.

When we arrived at Peckarna, they took us to the room where our father, grandfather and other people were. After some time, they marched us downstairs into the room which was called “cinema”. In the meantime, Aunt Hana had also been brought in. Mrs. Necas, the Neumann and Robetin families and others who had families abroad, were there. At the end of the day we were all pushed into a lorry with canvas curtains and driven away, but we did not know where to. Guessing from the direction of our drive, we knew that it was not Pankrac, but more likely Holesovice where dozens of people had been executed after the Heidrich assassination. (Their names are engraved there in remembrance). I sat opposite my father and I could see that he turned pale and started to sweat. He was obviously relieved when we did not stop and continued towards Terezin town which was then serving as a Gestapo concentration camp. From there people were spread to different camps or jails.

During our first night they made us stand against the wall in the first courtyard, read out our names and sent the women to the women’s section. From then on everything went like clockwork we could not believe. Our clothes were swapped for some old military uniforms, our hair (and even grandpa’s beard) was shaved off. We were allowed to keep only our shoes and some personal belongings. There were about 60 of us and we were accommodated in the third courtyard in a cell. We slept on plank beds, and there was only one Turkish lavatory and one water tap. Our cell was right next to the kitchen. Our verdict was “guilty of suspicion to be working against the benefit of the Reich” So we became enemies of the Reich. Next day we were sent to work, grandpa to the kitchen to peel potatoes, father who was disabled was sweeping the courtyards, and Karel and I were directed to work on the rail tracks. And that was it, no court, no proof, no “three days”. Nobody told us anything, so we knew nothing.

In the morning, the alarm went off at 5 o’clock, black slurry and piece of bread for breakfast, the roll call, walk to the train station, and then by train to Litomerice, where we worked extremely hard all day long. The first day I had a big burst blister on my right hand from helping Mirek (my cousin) to tile the floor of his swimming pool. I still had to work on with a spade and pickaxe. We had extremely poor soup for lunch. When we were working, SS men were always watching us and if anybody tried to straighten up and stopped working, he was beaten badly or bullied otherwise. In the evening we returned through the Hitlerjugend’s training airfield. Only when it was rainy, we would walk through the town which at that time was turned into a Jewish Ghetto. We witnessed how Jews were mistreated. Students from Roudnice were working with us, their grammar schools were shut down and academics laid off by Germans. They were probably as old as we were.

In the evening we were offered a watery soup with one or two potatoes. The worst thing about our accommodation was the always present fleas. I was bitten constantly, and I couldn’t even scratch myself as I was given some sort of riding breeches which were tight from the knees down. In the evenings we tried to get them out from under our clothes and we also helped my father and grandpa. It was impossible since there were hundreds of them, and my stings gradually inflamed and turned into boils. Now and then, some prisoners were taken into the factory “Schicht” where they squeezed oil from plants. From the remains we picked some grains if we could find some. However, at least the lunch time soup was better there. When we were marching through Litomerice, which after Munich agreement became part of the Reich, we watched reactions of locals. But there was no sign of any compassion or willingness to help us.

One day on our return from work, we saw our mother standing at the entrance. She came with the transport and was sent to the women’s part of the camp. It was a great surprise. She was arrested three days after us when she went to the Gestapo to get some information about us. She was kept for a while at Karlak and thereafter transported to Terezin together with Aunt Hana. To be able to see them we applied for a job of meal carriers and were bringing the buckets of food to the women’s section. The kitchen was next door to our cell, so it was easy, and it helped us to know that they were still there.

During my stay there I was moved several times from one section to another, for instance for a day or two I worked in the laundry which was next door to the women’s accommodation. Shortly afterwards I was sent to build a pool. I and everybody else there were always used for digging work. There I witnessed the cruellest behaviour of SS officers. We had to carry sacks of concrete or push a barrow with soil. The barrow had to be full, sometimes they poured water over it to make it heavier. Storch was the worst guard in this category, most likely because it was happening inside the fortress and civilians never saw that. Personally, I saw him torturing a Jew so long that he eventually beat him to death. Once when I was pushing a barrow which he thought was not full enough, he said something that I did not understand as he spoke with a heavy dialect. In the end he screamed at me “haul ab”, then he slapped my ears so hard that I lost my hearing for some time. Since then I remember exactly what “haul ab” means.

Fortunately, this happened only once throughout my stay, because I learned very quickly how to avoid situations which would draw attention and trigger off the rage of SS men. One of the prisoners was not so lucky. His name was Jedlicka and he was very tall and also very clumsy. He could hardly hold a spade. He suffered lots of beating. We learned later, when the war was almost over, that he committed suicide by jumping into the electric fence of the concentration camp he was sent to. I think it was Auschwitz.

The days working on pool digging with Storch and Rojka behind our backs were my worst days in Terezin. Not only was our work really exhausting, but I also saw many prisoners being tortured to death. The only human guard was Hofhaus in the food store. Once he even brought two eggs for grandpa, allegedly from the miller in Terezin. After the war he was put on trial and was granted amnesty. I was lucky because I was young, sporty, and strong enough in those first months so that I wasn’t conspicuous by a small output or clumsiness with tools.

We stayed at Terezin till the beginning of September. Then we were ordered to change back to our own clothes, loaded into a train and started our journey. Fortunately, all of us were still together. Nobody told us anything, so we did not know that we were going to Dachau. First stop was at Cheb where we arrived in the middle of the night in darkness. We got off the train and the next morning they tied us together and marched us to jail. No food or water was offered. My feet hurt very badly because of the flea bites. The cells were full of bedbugs. They got after us, they liked my brother Karel best, so he got more bites than me. Next day we were fed the usual watery soup with few potatoes. Not much but better than nothing.

Two days later we were again loaded onto a train and continued to Hof. At Hof they threw us in the cellar cell where there were no blankets or something to lay on. Also, no food or water. Next day we were driven to Nuremberg, still without any food. We were taken to an overcrowded gymnasium. There were straw mattresses on the floor with a waste bucket at the end. I was assigned the one next to the bucket. There was lots of uncertainty, hunger, chaos and fear, but at least we were still together, and that was important.

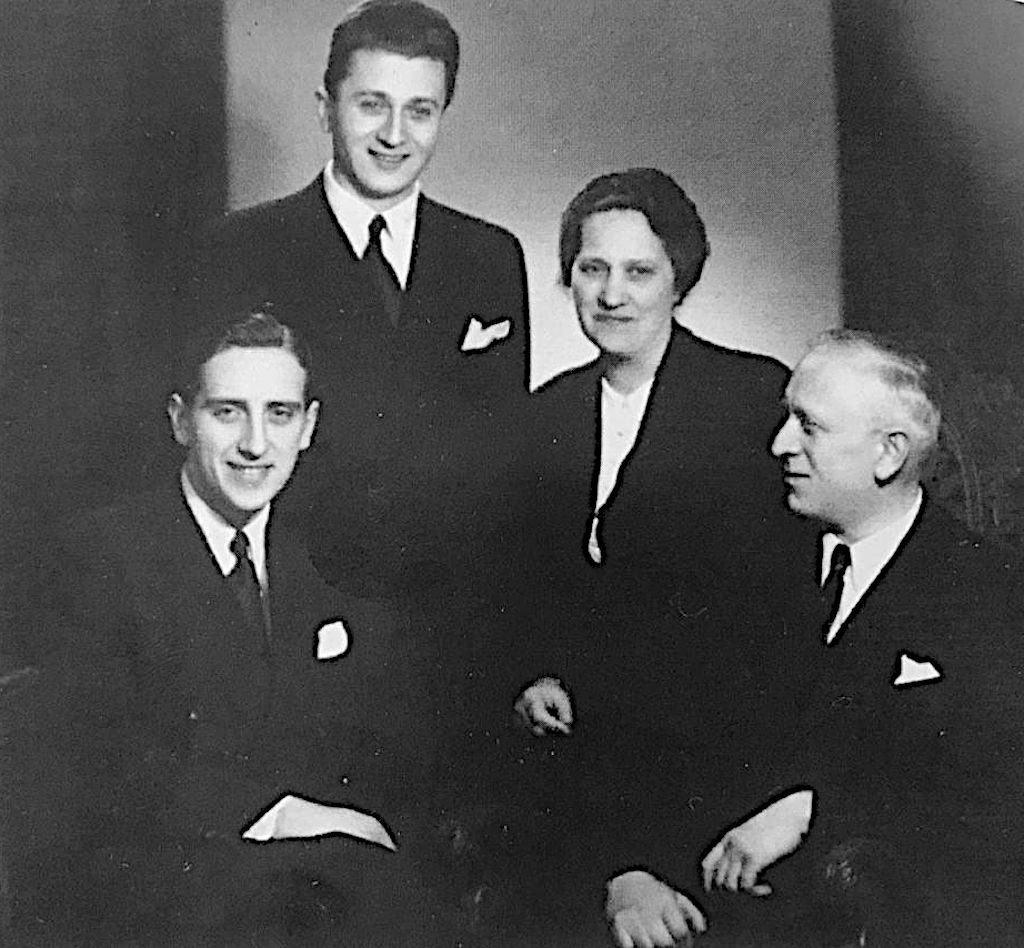

from the left: Vladimír Feierabend, his brother Karel Feierabend, mother Marie Feierabendová and father Karel Feierabend

Two days later we continued by train to Dachau. From the train station we were transported by lorries to the political section of Dachau concentration camp. There were lots of barracks build in rows with a path in the middle. At the entrance of the camp, we were photographed from all sides and had to fill in a questionnaire and personal details were drawn up. Then we quickly passed through a gate with the sign in German “Arbeit Macht Frei" (work liberates) and had to hand in all of our civilian clothes, watches and valuables (of which we had none). All this took place in the room in the main building. We were then shaved again (and this time everywhere were the human body has hair) and washed in creosol (=Dettol). It burned like hell. This was done to prevent lice and other bugs from spreading in the camp. After all this, we had a quick bath … (the first one in two months) and were given a number (mine was 36176) and fitted out with blue and white striped uniform and clogs. We were accommodated at section 15, room 3. There were people from all over the world including Germans. I could not find any of the Czech people we made friends with in Terezin or on our way to Dachau. I must admit that after our stay in Terezin and the very distressing transport, we all felt much better in Dachau. There were clean beds and blankets. We got a place for our food dish, towel, and personal items. The dormitory was separated from the dining room which was furnished with tables and small chairs (called “hockry” by us). The three stories bunk beds comprised straw mattresses, pillows and two blankets.

The first impressions of our life in the camp were quite positive, as well as the fact that I had the boils on my feet treated and Karel got rid of his diarrhoea which weakened his body during the transport. However, those first impressions quickly disappeared. The SS commanders and the “Kapos” (prison guards) were strict and pedantic. After the wake-up alarm we had to make our beds. They all had to look the same, all perfectly done without a wrinkle. If a prisoner did not comply, he didn’t get any breakfast. (black slurry and 200 gr. of bread). Then we marched outside, lined up and the roll call took place. Afterwards we had to clean the dormitory. After that we practiced some German marching songs which we would sing on our way to the Appellplatz or to work.

For lunch we got one litre of cabbage soup with 3 unpeeled potatoes. Same for dinner. Three times a week we had bread with a small piece of sausage or low-fat cottage cheese. On Sundays we got pasta with some sort of gravy with a few strings of meat. We spent our days by standing in line and learning the camp's songs and rules. In this quarantine block we met Raymond Schnabel who apologized to our grandpa for what Germans did to us. At that time grandpa was the oldest prisoner in the camp. He was bravely holding up. As far as our health was concerned, we were all doing pretty well. Because of the quarantine we were separated from the other Czech prisoners. Nobody was allowed to come to us. Sometimes we managed to talk to somebody over the wire fence.

After three weeks at the end of September we were transferred from the quarantine to the 10th block so called the Czech block. Luckily, they put all four of us together. For a while we had no work. We had time to learn from senior prisoners how to survive in the camp. When the potato season was over, we joined the "Baulager II" command and were sent to dig foundations to a building outside of the camp, but of course under the supervision of the SS men. It was already autumn with chilly weather and lots of rain. Often, we had to put on completely wet overalls.

In December, we changed commando again and got to the warehouse "Bekleidungslager", where the equipment for the SS division was stored. It was much more pleasant to be under the roof, especially because there were great possibilities for “organizing” things. In the store there were various things which were useful or even necessary for our camp life. For example, socks, pullovers, gloves, leather items which we were stealing with great risk and then exchanging for other merchandise we were short of, such as food. It was particularly important to hide those well so that the people who searched us, didn’t find them. If they caught somebody stealing, there were very heavy punishments. They would hang the man by his arms for a long period of the time, he got 25 lashes on his bottom with a bull’s tail (Ochsenschwanz), or he was locked up in a small dark room for a week or longer. But the risk paid off and we were gradually able to exchange our stolen items for food, mainly to support grandpa to stay in shape. Our socks, full of holes as well as our old pullovers, were sent to the front office and we got new ones for ourselves. It was barter without money. We exchanged everything that suited the other prisoners for things that we did not get again. It was mainly food, later also cigarettes. There was quite a big market for all possible items in the camp such as radios, distilled alcohol, prison clothes, shoes and so on…

In December of 1942, the work program for our family changed again. Grandpa stayed in the “Revier”, father was moved to “Effektenkammer” (an office where clothes and private belongings were confiscated from newcomers that would be handed back when discharged.) It was a very pleasant job compared to others. It was inside and warm. My brother Karel stayed at the clothes store (Bekleidungslager) and I was sent to the Political sector, apparently after some contest in calligraphy.

At that time, the Political sector was represented by three workers. The head of this department was Arthur Lang (a Bavarian German with a black lapel), an émigré (cannot remember his name, with a blue lapel) and myself (with a red one). What an interesting group we were. In the beginning I would write the names and personal data of the newcomers by hand for Gestapo records. Later, when I learned how to use the typing machine, I did it that way.

The newcomer was first checked-in at the political department outside the camp, including photographing and completing a questionnaire and a resumé. It happened with gross bullying. After arriving inside the camp through the gate with the inscription "Arbeit Macht Frei", the newcomers had to remain for some time at the Appelplatz. Depending on the size of the group, they came to the area in front of the bath area. First, they had to undress completely. Their clothes were put in paper bags, they were deprived of all valuables (which were registered on a form, and were left with only personal belongings, such as toothbrushes, glasses, etc) Subsequently they went naked to answer the list of personal questionnaires, which we did from the political department, where they were assigned prison numbers. I was not very good at it in the beginning. Later I managed to write a questionnaire in all world languages, except English. Basic information was entered in the questionnaire, i.e. name, surname, residence, closest relatives, religion. Slavic languages were not a problem: I could speak German and French. The worst was Hungarian. After completing the questionnaire, the newcomers proceeded to the bath area, and after bathing received striped prison clothes and clogs, and were taken over by the head of the block or the writer (administrator of the block and usually taken to quarantine first. During the last year there was a shortage of striped Lager uniforms, consequently civilian clothes started to be used, mainly from dead prisoners. They had cut out holes in the back covered with a cross of fabric or painted cross.

In 1944, during an Allied raid, an incendiary bomb fell on the roof of the administration building, where all clothes were stored, and all were burned. Despite the short time I worked there, I had access to some important information. I had an overview of Czech prisoners and could warn them in time when compiling transports to other concentration camps so that they could try to avoid them during the selection and not succumb to the various SS practices they used in the selection. It was always better to stay in known environment, with friends around, who were willing to help. Each move to a new camp brought new dangers. Traveling for several days without food in terrible hygienic conditions and overcrowded cattle cars, sometimes uncovered, infested with lice infection, and even the stress of uncertainty of the new environment, was very unpleasant. Many prisoners did not survive these transports, and the closer the end of the war approached, the worse transport conditions were.

On January 20th I contracted typhoid. I am not sure where I got infected. Most likely from receiving the newcomers. The epidemic quickly spread to the entire camp. About 1000 prisoners got infected. We were isolated in the camp’s hospital. I ran a fever over 40 degrees Celsius for 4 weeks. As a young man, I was placed upstairs in the highest of the three-story bunk bed. Perhaps it was my luck that I did not notice much during those high fevers since the room was overcrowded and stank extremely, since some people didn’t always make it to the bathroom. It was really hard for me to climb back to my bed, because my body was very weak. Moreover, it was depressing to see people suffering and dying all over the place, not receiving any help. The bathroom area wasn’t heated in the winter, so the pneumonia also joined in. The medical treatment was very poor, and we had to be on a strict diet. If I remember correctly, I got only about 20 cc of liquid glucose once, and that was it. So, it was a question if my body would last or not. I was lucky that I was young and strong, so my body was able to fight typhus and I survived.

My brother and my father organized help for me from outside. It was amazing to see the solidarity of other prisoner for the ill. They helped with crackers, jam or lemons and we slowly got back on our feet. Then we were moved to the 17th block to recover. We did not have to work for one month. At that time the German approach to the use of prisoners began to change. It was after Stalingrad and Germany needed to secure the war's production of labour to replace those who had been lined up to fight. The approach of the SS leadership had also changed. The senseless atrocities of their members had diminished. We could receive food packages from home which supplemented the calorically poor and monotonous camp diet only partially. They meant a connection with home, and even that had a positive effect. Today I really admire the relatives who, at high risk, with a rigid ticket system, found a way to send suitable food to the camp that would withstand transportation. For sure, it was not easy. I survived typhoid and returned to the same commando, to the political block.

The year 1943 was therefore relatively more favourable for us in terms of survival. We all believed that the war was coming to an end and that Germany would be defeated. The important thing was that all 4 of us stayed in the camp. Grandpa was still in the hospital in the care of nurses under the supervision of Dr. Bláhy and other Czech medics, father remained in the commando department, which recorded all things that were taken away from the prisoners on arrival, as evidence of German neatness. My mother in Ravensbrück and I were able to correspond, so the whole family knew that we were at least alive, which was encouraging and reassuring for all of us. The camp became more and more crowded, so we had to sleep two in one bed. It was not very comfortable, and we had to learn to sleep stretched. Hygiene and diet deteriorated. Prisoners, especially the newcomers, were no longer exclusively dressed in uniform striped suits, but also in civilian clothes, apparently taken from the deaths. The modification consisted either in a coloured cross on the back with indelible paint, or through artificially created holes with a sewn-in cloth cross.

And so, the year 1944 began. Hard labour was terrible. Mortality increased due to exhaustion and malnutrition, especially with newcomers, weakened after transports from other camps. On the other hand, some relaxation of the camp regime brought more freedom and free time. We were allowed to play football, organize concerts of a prison band, watch German films and cultural programs were organized.

The constant need for new labour led to the construction of new branch camps. The main camps were Kaufering and Mühldorf, in the neighborhood of Munich. Jews from all over Europe were brought there to build underground aircraft factories. I had the opportunity to see their arrival because I was sent there to register them in the records of the mother camp. They lived in dugouts, without the possibility of maintaining hygiene. Harsh working conditions led to their "destruction by work" instead of by the gas chambers.

The Allied invasion of June 1944 and further advance in the East brought new hope that the war would end soon. After the invasion, thousands of Frenchmen, members of the underground movement, who had been locked up in the local camps, especially in Compiegne, were moved to Dachau. The conditions of these transports were so appalling that only 20 percent of the entire transport arrived alive in Dachau. The capacity of the camp was thus further exceeded to such an extent that they were transferred to other camps, thus further deteriorating their health. We were hoping that the war would be over before Christmas, but it did not happen.

In the increasing chaos we were now strictly guarded, men aiming machine guns at us from all the towers. To attempt escape would equal suicide. At the turn of 1944-45, due to unbearable hygienic conditions, an epidemic of typhus, transmitted by lice, broke out in the camp. No wonder. It was not possible to change the laundry or wash it. The contact between the people in the crowded barracks was awfully close and could not be avoided, even though we checked the laundry every day to see if we could find any lice. The infection spread to civilians with whom prisoners worked. The situation worsened even at the beginning of 1945, when there were severe frosts, there was no fuel, and food provisions collapsed. The epidemic killed over 14,000 prisoners. Some of them unfortunately died even after the liberation of the camp. The crematorium could not cope, and people had to be buried in mass graves. And yet in the spring of 1945 more transports were coming to Dachau from camps which were evacuated because of the advancing front. They were mostly prisoners completely exhausted by the long marches of death, walking for miles without food and drink. Who could not go on, was shot.

Vladimir 1945

And so, the evacuation of Dachau was prepared in April. The evacuation was directed to go to the Alps, where the Germans expected to hold on. Negotiations were held with the International Red Cross. Nevertheless, 3 transports were prepared and left the camp. However, some returned in the confusion at the end of April. There was still gunfire and the rumble of advancing Allies. The line was approaching. Will we survive or be shot or burned in barracks, like in Kaufering, as witnesses to Nazi barbarism? But they no longer had the strength. All SS leaders disappeared from the camp, and a riot broke out in Dachau, organized by escaped prisoners. It was bloodily suppressed.

Then came 29 April. There were only three guards left on the towers. Suddenly an American jeep appeared at the gate. I cannot describe our happiness and relieve. Dachau concentration camp was liberated by the 42-45 division of 7th American army. At the time there were 30,000 prisoners in the main camp and another 35,000 in its branches. Unfortunately, the typhoid epidemic was not yet over. The Americans ordered a 3-week quarantine period. However, in a quickly developing chaos, some prisoners were able to escape, and they started to walk back home.

My brother Karel was one of them. He got to Prague and arranged some coaches which would take the Czech prisoners home. After three weeks of quarantine, the Americans opened the camp and arranged lorries which transported all Czech prisoners to Pilsen. From there everybody had to continue home on his own.

I arrived in Prague on 22 May together with my brother. The next day we were reunited with mother and Aunt Hana who both survived Ravensbrück. Their journey home had been very difficult.

Ravensbrück was evacuated on April 20th, but their transport got into a war zone and was dispersed. A group of Czech women walked all the way home. On the way they met some Czech men who were also aiming for home and after a very adventurous journey they arrived at Jablonne v Podjestedi on 23 May where the Mayor of the town organized a bus which took them home the same day.

Father arrived the next day in an American transport. And Grandpa, exhausted but alive, was taken to Pilsen by the Americans. I picked him up there by taxi a drove him straight to Vinohrady hospital, but despite of all care he died on 6 June.

Happily, we all survived Dachau. Why use the term “happiness”? We were happy not succumbing to SS terror, staying healthy and overcoming illness, staying in one camp, getting into a good commando and to have good friends around you. But last but not least, we never gave up.

My brother and myself were young, happy, and content, so it was easier for us to survive those three years. After all our family got back together and we could continue with our civilian lives. I started school on June 15 to finish my high school diploma and be able to apply for medical studies. My brother started studying engineering, my father returned to the Directorate of Railways and my mother stayed at home. In this way things continued until 1948, when our family was affected by communist totalitarianism. But that is another story.

Vladimir Feierabend 2013 Dachau.